Blog – by Samuel Edward Taylor, The Underfall Boatyard

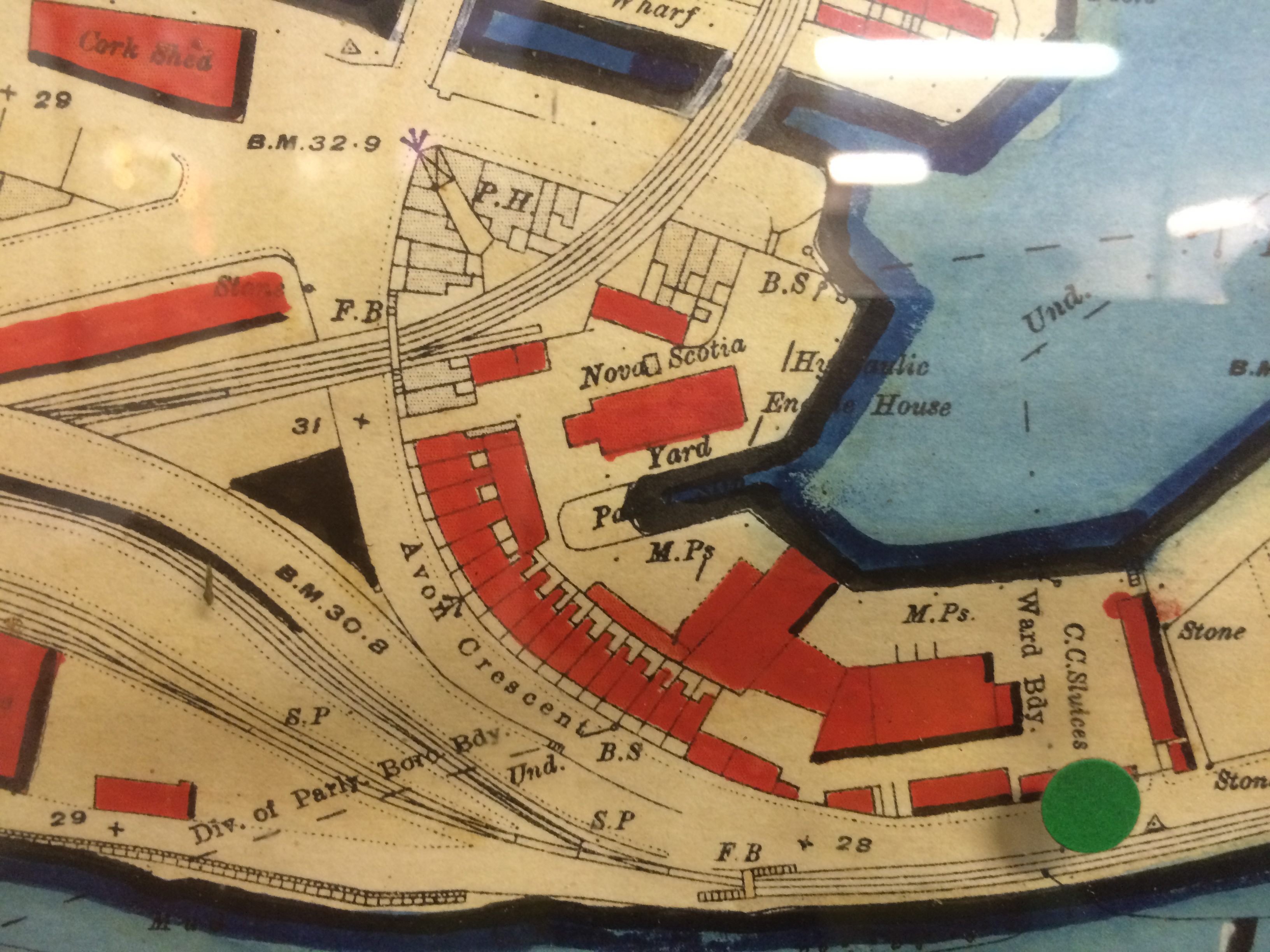

The UnderFall Yard has an exceptionally interesting history but I’m not going to embarrass myself (or the wonderful people who work there) with a series of inevitable inaccuracies, so for a comprehensive understanding of it’s history check out underfallboatyard.co.uk or alternatively contact Nicola Dyer (Project Manager) or Sarah Murray (Community and Learning Officer) via the site or Twitter (@theunderfall) who do a brilliant job explaining the vital function of the yard as well as it’s fascinating place in Bristol’s heritage.

…

So before I knew anything about the Floating Harbour I was pretty pleased when I found out from Rachel (Part Exchange Co) that my ‘site’ would be The Underfall. I’ve always had this idea of making a show set on a boat. A while back I got sort of obsessed with the story of Flora MacDonald and Bonnie Prince Charlie and their escape from Uist to the Isle of Skye after the Battle of Culloden… Jacobean Scotland is a bit of a side step from Brunellian Bristol I know, but I’ve always fancied the idea of making an intimate, site specific show that was ‘on the water’ so to speak, and that was about escaping, maybe, or making a new start. I guess water, and a sense of below-ness (depth I think they call it!) sort of lends an immediacy in terms of story telling that gets me going.

…

So one thing (there were many) about the yard that really took flight in my imagination came from a conversation with Sarah (Community and Learning officer) and Ray Davies (volunteer and retired blacksmith who worked at Underfall for 40+ years), who told me that the hydraulics in the Sluice Room had the capability to empty the floating harbour of it’s water. It was sort of an innocuous fact until Sarah pointed out that because the walls of the harbour have pressed against the pressure of the water for so long – and that the stone will have been weakened by this – that if the harbour was drained the walls would fall. Hotwells and other areas along the water would collapse into the river bed.

I’ve been writing for screen recently, which is a totally new thing for me, and the movie pitch generator I’ve been developing in my head got to work and started to imagine a disaster movie set in Bristol, where some evil person(s) intentionally emptied the river and sat back as havoc ensued and the residents of BS8 and co struggled to deal with the consequences.

I’m not going to write that movie. I’m not even going to write that pitch. It’s a terrible idea and onthe day my immediate response to the site was effected by me having been engaged in film and TV and not theatre mode for the last few weeks but in retrospect (and absolutely in a more subtle sense) I’ve been thinking about the control the water holds over the city. The writing in response to the site which I read at the end of the day was a sort of sketch of what the disaster element of what that film might feel like. It was meant to be a bit of fun and it was arch and farcical (mostly because I left the writing part of the residency until the end of the day!) but the simple act of reading an idea aloud to a group of people I didn’t know helped me bridge back into live/theatre mode (there are definatly modes btw) It also got me thinking about the unseen forces at play in the city and how I might use that sense of depth and control that the water has over us to tell a story in a new way, maybe in a new place. I’m not quite sure what the idea might be yet, it needs time to brew, but if I had to sketch out a terrible disaster movie to get there then that’s fine – and I should thank Sarah and Ray for setting me on the right path.

Performance Text – by Samuel Edward Taylor, The Underfall Boatyard

Ideas for the opening act of a disaster movie

Scene 1

This is where it happened.

Where they broke in.

They used bolt-cutters and a tarmac drill to take the

door off it’s hinges.

It took maybe 10 seconds.

And they were inside.

They came as a four.

One climbed the tower to keep watch over the road

and along the river.

One kept outside and watched the gate.

One stood at the pressure gauge.

The last one turned the switch.

And it had begun.

As they left one of them stuck a note on the control

panel.

“BRISTOL, YOU HAVE BEEN DRAINED.”

…

Scene 2

The city was quiet at three o’clock on a Monday

morning.

The river was calm.

Nobody about.

There were birds and there was birdsong.

There were a few cars.

A handful of people off to the airport for an early flight

maybe.

More lorries than cars actually.

Lorries from Mainland Europe whose drivers have

been driving for hours and hours and don’t see the

point of stopping this late, or this early.

A few postmen and postwomen cycled past, but they

kept their eyes fixed firmly on the road.

The only people on the river were those all cosied up

in house boats, most definitely all asleep.

Nobody noticed.

Nobody stirred.

The water line in the harbour was dropping.

…

Scene 3

A man stepped out onto the balcony of his riverside

apartment.

Couldn’t sleep.

He lit a cigarette.

He looked out at the river.

He looked at the abandoned trawler moored across

the way.

The hull looked bigger than usual.

Boat looked taller.

Fatter.

He must of been tired.

He went back to bed.

…

Scene 4

By the time the buses were running the sun had

risen.

The city was waking up.

The four people who broke in here last night were a

hundred miles away at least, headed to a different

city.

In the van they talked about what they’d done.

What they’d started.

They switched on the radio and waited.

…

It’s surprising how many didn’t take any notice.

It was only when someone pointed out.

It was only when a crowd started to build.

It was only when the TV people turned up.

Where did it go?

Where is the water?

…

Scene 5

The police blocked off and taped the sluice room.

Forensics took what they could but there were no

prints.

Some yard workers were taken into custody.

Questions were asked.

Motives were analysed.

Background checks completed.

The harbour master insisted that the city needed to

be evacuated.

The guys from special branch laughed at him.

The news reporter made a joke at his expense.

His wife text and told him to stop making an idiot of

himself on breakfast television.

But he insisted.

He said when the harbour loses that much water it’s

a dangerous thing.

The harbour walls are only strong with the pressure

of the water up against them.

He said they needed to start with Hotwells and then

everywhere along the river.

He said Clifton wasn’t safe either.

He said to get them out.

…

Scene 6

Past breakfast and the water was now all gone.

The mayor did a live broadcast.

And a Tweet.

He said to keep calm.

He said the harbour master was over excited and

was enjoying his fifteen minutes.

They’d sort the water out.

Everyone, get back to work.

…

Scene 7

The harbour master, resigned from his efforts at

warning the city, went home.

He’d warned as many folks as possible .

He’d lived on the river all his life but he was packing

up now.

He told his wife to do the same.

She was reluctant at first then she saw a look on his

face she’d never seen before.

Hand in hand they walked out of their riverside

cottage for the final time.

…

The water had left the contents of its belly behind.

Office workers came out with their coffees to take

photos.

All manor of filth and silt.

Plastic.

Bricks.

Dirt.

Wood.

Bones.

…

Scene 8

When the first crack appeared nobody said a thing.

It’d be sorted.

There’d be a plan.

When the first bricks fell it must’ve been expected.

There must be procedure

When the soggy walls of Hotwells buckled and folded

onto the river bed people still stood watching.

A row of houses followed suit.

The pub, gone.

The kebab shop, gone.

The garage, gone.

The streets behind, gone.

The road wasn’t there anymore.

The river bed proudly displayed its own collection of

hatchbacks.

…

Scene 9

The cameras filmed as hundreds and hundreds and

hundreds of people fled the scene.

Folks lost their balance as the tremors from beneath

the ground split pavements and the hills above the

gorge started to look shaky too.

The townhouses of Clifton slipped as gracefully as

they could down the hillside.

…

Scene 10

The harbour master and his wife had reached Ashton

before they dared to turn and look back at what was

left of their home.

Comments are closed